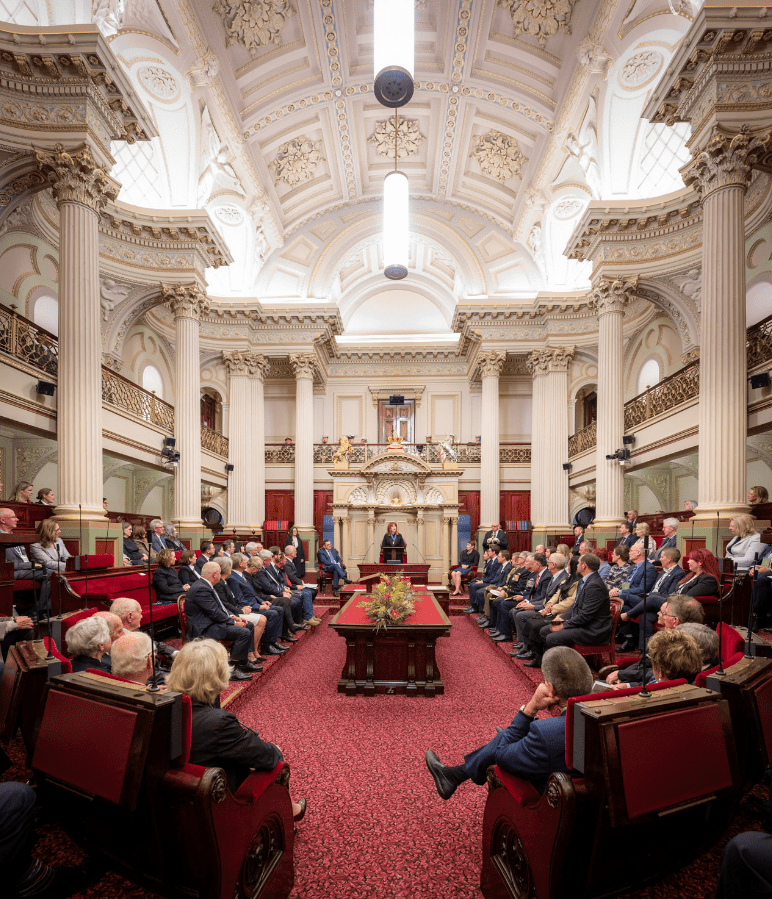

Speech given by Her Excellency at her inauguration as Victoria's 30th Governor.

I begin by acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the lands on which this House stands – the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung of the Eastern Kulin – and pay my respects to their Elders, past and present.

And I pay my respects to any other Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people present today.

I am deeply honoured to be the 30th Governor of Victoria.

This State is a place so ancient and yet so new. The connection to land of those who are of the many continuing Aboriginal groups in Victoria is different in kind from that of others - including the people who came following European colonization, and those who have arrived since then from across the globe, whether migrant or refugee.

Yet I believe we all recognise the land so aptly described by Victorian-born Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson - better known by her pseudonym Henry Handel Richardson.

“…the scanty, ragged foliage; the unearthly stillness of the bush; …the colours in the apparent colourlessness; ...the blue in the grey of the new leafage; the geranium red of young scrub; the purple-blue depths of the shadows. To know … a rank nostalgia for the scent of the aromatic foliage;… the honey fragrance of the wattle; … - even … the sting and tang of countless miles of bush ablaze…”

This is a Victoria we know and wish to conserve. We wish to better engage with the connections Victoria’s Aboriginal peoples have to this land.

And I believe, the role of Governor can play a part in this engagement within the constitutional fabric of this State.

Ours is a constitutional fabric that has been shaped by a democratic impulse - a democratic impulse that has driven Victoria ever since our Separation from New South Wales in 1850.

From the vantage point of 2023, we may forget that the story of Victoria is a story of people demanding to be heard.

Victorians asked to be heard when they sought self-governance.

Victorians on the Ballarat Gold Fields demanded to be heard on November 11, 1854, when – in their thousands – they voted in support of the Ballarat Reform League Charter.

That Charter – which was presented to Victoria’s first Governor, Sir Charles Hotham – is the nearest Australia has to a Declaration of Independence.

The handwritten copy of the Charter – made by one of Governor Hotham’s clerks – is a manifesto of democratic principles and demands.

Among those demands:

‘That it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he or she is called upon to obey.’

There it is again: voices demanding to be heard.

That democratic impulse was partly realised after the Eureka Stockade, when Victoria cleared the way for men without property to vote. This at a time when owning property was usually the only way to be heard in parliaments across the world.

That democratic impulse was partly realised again in 1908 when – following a 39-year battle – women in Victoria won the right to vote.

Female suffrage only came after a momentous campaign – including the presentation of a monster petition measuring 260 metres in length – as well as 19 attempts to pass legislation through the Victorian Legislative Council.

Those Victorian suffragettes were persistent.

They did not stop until their voices were heard.

However, while the democratic advances of 1857 included all male Victorians - including Victoria’s male First People, the right to vote at federal elections set in 1902 excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. The franchise was not extended to all women and men in Victoria until 1962.

The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria, which is today working to ensure the voices of Aboriginal peoples in this State are heard, is part of a democratic Victorian tradition.

I want to acknowledge the newly elected Co-Chairs of the Assembly – Ngarra Murray and Reuben Berg – and wish them success.

We might imagine the work of the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria as a chance for our State to – after 169 years – fully realise the ambitions of the Ballarat Reform League Charter.

That Charter spoke to universal rights that took many years to secure.

Victoria now embraces all its citizens, and we can see the contours of modern Victoria in the diversity of those at the Eureka Stockade.

Of the miners detained after the Eureka Stockade battle, only three were born in the Australian colonies.

The other miners, some 100 or so, were from Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Italy, Corsica, Greece, Germany, Russia, Holland, France, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Sweden, the United States, Canada, and the West Indies.

The Southern Cross flag was designed by a migrant.

The first miner tried for treason (and acquitted) – John Joseph – was African-American.

On this ancient land, there is no typical Victorian – this State is a place of many peoples and many cultures. In the time before colonisation, Aboriginal peoples spoke more than thirty different languages here.

There is ample space for the new and the ancient.

There is room for the light that comes from many voices being heard.

Victoria is a place of many people and many voices where, by listening to the experiences of those voices, we can and shall grow wiser.

That is why, as Governor, I look forward to being part of the journey with the people of Victoria as our future unfurls.

I look forward to hearing your voices and learning from your experiences, and being part of ensuring your democratic institutions and your democratic impulse are supported and preserved.